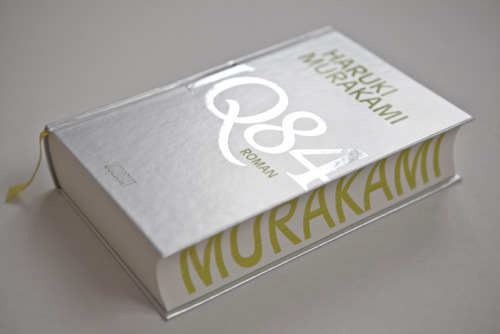

I fan di Murakami attendono con impazienza da più di un anno la traduzione italiana del suo ultimo grande romanzo, 1q84, che dovrebbe teoricamente uscire in autunno per i tipi dell’Einaudi. Per placare momentaneamente la loro fame, propongo oggi un lungo brano pubblicato in inglese da <<The New Yorker>>, tratto proprio da 1q84, e intitolato Town of Cats. Buona lettura.

At Koenji Station, Tengo boarded the Chuo Line inbound rapid-service train. The car was empty. He had nothing planned that day. Wherever he went and whatever he did (or didn’t do) was entirely up to him. It was ten o’clock on a windless summer morning, and the sun was beating down. The train passed Shinjuku, Yotsuya, Ochanomizu, and arrived at Tokyo Central Station, the end of the line. Everyone got off, and Tengo followed suit. Then he sat on a bench and gave some thought to where he should go. “I can go anywhere I decide to,” he told himself. “It looks as if it’s going to be a hot day. I could go to the seashore.” He raised his head and studied the platform guide.

At Koenji Station, Tengo boarded the Chuo Line inbound rapid-service train. The car was empty. He had nothing planned that day. Wherever he went and whatever he did (or didn’t do) was entirely up to him. It was ten o’clock on a windless summer morning, and the sun was beating down. The train passed Shinjuku, Yotsuya, Ochanomizu, and arrived at Tokyo Central Station, the end of the line. Everyone got off, and Tengo followed suit. Then he sat on a bench and gave some thought to where he should go. “I can go anywhere I decide to,” he told himself. “It looks as if it’s going to be a hot day. I could go to the seashore.” He raised his head and studied the platform guide.

At that point, he realized what he had been doing all along.

He tried shaking his head a few times, but the idea that had struck him would not go away. He had probably made up his mind unconsciously the moment he boarded the Chuo Line train in Koenji. He heaved a sigh, stood up from the bench, and asked a station employee for the fastest connection to Chikura. The man flipped through the pages of a thick volume of train schedules. He should take the 11:30 special express train to Tateyama, the man said, and transfer there to a local; he would arrive at Chikura shortly after two o’clock. Tengo bought a Tokyo-Chikura round-trip ticket. Then he went to a restaurant in the station and ordered rice and curry and a salad.

Going to see his father was a depressing prospect. He had never much liked the man, and his father had no special love for him, either. He had retired four years earlier and, soon afterward, entered a sanatorium in Chikura that specialized in patients with cognitive disorders. Tengo had visited him there no more than twice—the first time just after he had entered the facility, when a procedural problem required Tengo, as the only relative, to be there. The second visit had also involved an administrative matter. Two times: that was it.

The sanatorium stood on a large plot of land by the coast. It was an odd combination of elegant old wooden buildings and new three-story reinforced-concrete buildings. The air was fresh, however, and, aside from the roar of the surf, it was always quiet. An imposing pine grove formed a windbreak along the edge of the garden. And the medical facilities were excellent. With his health insurance, retirement bonus, savings, and pension, Tengo’s father could probably spend the rest of his life there quite comfortably. He might not leave behind any sizable inheritance, but at least he would be taken care of, for which Tengo was tremendously grateful. Tengo had no intention of taking anything from him or giving anything to him. They were two separate human beings who had come from—and were heading toward—entirely different places. By chance, they had spent some years of life together—that was all. It was a shame that it had come to that, but there was absolutely nothing that Tengo could do about it.

Tengo paid his check and went to the platform to wait for the Tateyama train. His only fellow-passengers were happy-looking families heading out for a few days at the beach.

Most people think of Sunday as a day of rest. Throughout his childhood, however, Tengo had never once viewed Sunday as a day to enjoy. For him, Sunday was like a misshapen moon that showed only its dark side. When the weekend came, his whole body began to feel sluggish and achy, and his appetite would disappear. He had even prayed for Sunday not to come, though his prayers were never answered.

When Tengo was a boy, his father was a collector of subscription fees for NHK—Japan’s quasi-governmental radio and television network—and, every Sunday, he would take Tengo with him as he went door to door soliciting payment. Tengo had started going on these rounds before he entered kindergarten and continued through fifth grade without a single weekend off. He had no idea whether other NHK fee collectors worked on Sundays, but, for as long as he could remember, his father always had. If anything, his father worked with even more enthusiasm than usual, because on Sundays he could catch the people who were usually out during the week.

Tengo’s father had several reasons for taking him along on his rounds. One reason was that he could not leave the boy at home alone. On weekdays and Saturdays, Tengo could go to school or to day care, but these institutions were closed on Sundays. Another reason, Tengo’s father said, was that it was important for a father to show his son what kind of work he did. A child should learn early on what activity was supporting him, and he should appreciate the importance of labor. Tengo’s father had been sent out to work in the fields on his father’s farm, on Sunday like any other day, from the time he was old enough to understand anything. He had even been kept out of school during the busiest seasons. To him, such a life was a given.

Tengo’s father’s third and final reason was a more calculating one, which was why it had left the deepest scars on his son’s heart. Tengo’s father was well aware that having a small child with him made his job easier. Even people who were determined not to pay often ended up forking over the money when a little boy was staring up at them, which was why Tengo’s father saved his most difficult routes for Sunday. Tengo sensed from the beginning that this was the role he was expected to play, and he absolutely hated it. But he also felt that he had to perform it as cleverly as he could in order to please his father. If he pleased his father, he would be treated kindly that day. He might as well have been a trained monkey.

Tengo’s one consolation was that his father’s beat was fairly far from home. They lived in a suburban residential district outside the city of Ichikawa, and his father’s rounds were in the center of the city. At least he was able to avoid doing collections at the homes of his classmates. Occasionally, though, while walking in the downtown shopping area, he would spot a classmate on the street. When this happened, he ducked behind his father to keep from being noticed.

On Monday mornings, his school friends would talk excitedly about where they had gone and what they had done the day before. They went to amusement parks and zoos and baseball games. In the summer, they went swimming, in the winter skiing. But Tengo had nothing to talk about. From morning to evening on Sundays, he and his father rang the doorbells of strangers’ houses, bowed their heads, and took money from whoever came to the door. If people didn’t want to pay, his father would threaten or cajole them. If they tried to talk their way out of paying, his father would raise his voice. Sometimes he would curse at them like stray dogs. Such experiences were not the sort of thing that Tengo could share with friends. He could not help feeling like a kind of alien in the society of middle-class children of white-collar workers. He lived a different kind of life in a different world. Luckily, his grades were outstanding, as was his athletic ability. So even though he was an alien he was never an outcast. In most circumstances, he was treated with respect. But whenever the other boys invited him to go somewhere or to visit their homes on a Sunday he had to turn them down. Soon, they stopped asking.

Born the third son of a farming family in the hardscrabble Tohoku region, Tengo’s father had left home as soon as he could, joining a homesteaders’ group and crossing over to Manchuria in the nineteen-thirties. He had not believed the government’s claims that Manchuria was a paradise where the land was vast and rich. He knew enough to realize that “paradise” was not to be found anywhere. He was simply poor and hungry. The best he could hope for if he stayed at home was a life on the brink of starvation. In Manchuria, he and the other homesteaders were given some farming implements and small arms, and together they started cultivating the land. The soil was poor and rocky, and in winter everything froze. Sometimes stray dogs were all they had to eat. Even so, with government support for the first few years they managed to get by. Their lives were finally becoming more stable when, in August, 1945, the Soviet Union launched a full-scale invasion of Manchuria. Tengo’s father had been expecting this to happen, having been secretly informed of the impending situation by a certain official, a man he had become friendly with. The minute he heard the news that the Soviets had violated the border, he mounted his horse, galloped to the local train station, and boarded the second-to-last train for Da-lien. He was the only one among his farming companions to make it back to Japan before the end of the year.

After the war, Tengo’s father went to Tokyo and tried to make a living as a black marketeer and as a carpenter’s apprentice, but he could barely keep himself alive. He was working as a liquor-store deliveryman in Asakusa when he bumped into his old friend the official he had known in Manchuria. When the man learned that Tengo’s father was having a hard time finding a decent job, he offered to recommend him to a friend in the subscription department of NHK, and Tengo’s father gladly accepted. He knew almost nothing about NHK, but he was willing to try anything that promised a steady income.

At NHK, Tengo’s father carried out his duties with great gusto. His foremost strength was his perseverance in the  face of adversity. To someone who had barely eaten a filling meal since birth, collecting NHK fees was not excruciating work. The most hostile curses hurled at him were nothing. Moreover, he felt satisfaction at belonging to an important organization, even as one of its lowest-ranking members. His performance and attitude were so outstanding that, after a year as a commissioned collector, he was taken directly into the ranks of the full-fledged employees, an almost unheard-of achievement at NHK. Soon, he was able to move into a corporation-owned apartment and join the company’s health-care plan. It was the greatest stroke of good fortune he had ever had in his life.

face of adversity. To someone who had barely eaten a filling meal since birth, collecting NHK fees was not excruciating work. The most hostile curses hurled at him were nothing. Moreover, he felt satisfaction at belonging to an important organization, even as one of its lowest-ranking members. His performance and attitude were so outstanding that, after a year as a commissioned collector, he was taken directly into the ranks of the full-fledged employees, an almost unheard-of achievement at NHK. Soon, he was able to move into a corporation-owned apartment and join the company’s health-care plan. It was the greatest stroke of good fortune he had ever had in his life.

Young Tengo’s father never sang him lullabies, never read books to him at bedtime. Instead, he told the boy stories of his actual experiences. He was a good storyteller. His accounts of his childhood and youth were not exactly pregnant with meaning, but the details were lively. There were funny stories, moving stories, and violent stories. If a life can be measured by the color and variety of its episodes, Tengo’s father’s life had been rich in its own way, perhaps. But when his stories touched on the period after he became an NHK employee they suddenly lost all vitality. He had met a woman, married her, and had a child—Tengo. A few months after Tengo was born, his mother had fallen ill and died. His father had raised him alone after that, while working hard for NHK. The End. How he happened to meet Tengo’s mother and marry her, what kind of woman she was, what had caused her death, whether her death had been an easy one or she had suffered greatly—Tengo’s father told him almost nothing about such matters. If he tried asking, his father just evaded the questions. Most of the time, such questions put him in a foul mood. Not a single photograph of Tengo’s mother had survived.

Tengo fundamentally disbelieved his father’s story. He knew that his mother hadn’t died a few months after he was born. In his only memory of her, he was a year and a half old and she was standing by his crib in the arms of a man other than his father. His mother took off her blouse, dropped the straps of her slip, and let the man who was not his father suck on her breasts. Tengo slept beside them, his breathing audible. But, at the same time, he was not asleep. He was watching his mother.

This was Tengo’s photograph of his mother. The ten-second scene was burned into his brain with perfect clarity. It was the only concrete information he had about her, the one tenuous connection his mind could make with her. He and she were linked by this hypothetical umbilical cord. His father, however, had no idea that this vivid scene existed in Tengo’s memory, or that, like a cow in a meadow, Tengo was endlessly regurgitating fragments of it to chew on, a cud from which he obtained essential nutrients. Father and son: each was locked in a deep, dark embrace with his own secrets.

As an adult, Tengo often wondered if the young man sucking on his mother’s breasts in his vision was his biological father. This was because Tengo in no way resembled his father, the stellar NHK collections agent. Tengo was a tall, strapping man with a broad forehead, a narrow nose, and tightly balled ears. His father was short and squat and utterly unimpressive. He had a small forehead, a flat nose, and pointed ears like a horse’s. Where Tengo had a relaxed and generous look, his father appeared nervous and tightfisted. Comparing the two of them, people often openly remarked on their dissimilarity.

Still, it was not their physical features that made it difficult for Tengo to identify with his father but their psychological makeup. His father showed no sign at all of what might be called intellectual curiosity. True, having been born in poverty he had not had a decent education. Tengo felt a degree of pity for his father’s circumstances. But a basic desire to obtain knowledge—which Tengo assumed to be a more or less natural urge in people—was lacking in the man. He had a certain practical wisdom that enabled him to survive, but Tengo could discern no hint of a willingness in his father to deepen himself, to view a wider, larger world. Tengo’s father never seemed to suffer discomfort from the stagnant air of his cramped little life. Tengo never once saw him pick up a book. He had no interest in music or movies, and he never took a trip. The only thing that seemed to interest him was his collection route. He would make a map of the area, mark it with colored pens, and examine it whenever he had a spare moment, the way a biologist might study chromosomes.

Tengo, by contrast, was curious about everything. He absorbed knowledge from a broad range of fields with the efficiency of a power shovel scooping earth. He had been regarded as a math prodigy from early childhood, and he could solve high-school math problems by the time he was in third grade. Math was, for young Tengo, an effective means of retreat from his life with his father. In the mathematical world, he would walk down a long corridor, opening one numbered door after another. Each time a new spectacle unfolded before him, the ugly traces of the real world would simply disappear. As long as he was actively exploring that realm of infinite consistency, he was free.

While math was like a magnificent imaginary building for Tengo, literature was a vast magical forest. Math stretched infinitely upward toward the heavens, but stories spread out before him, their sturdy roots stretching deep into the earth. In this forest there were no maps, no doorways. As Tengo got older, the forest of story began to exert an even stronger pull on his heart than the world of math. Of course, reading novels was just another form of escape—as soon as he closed the book, he had to come back to the real world. But at some point he noticed that returning to reality from the world of a novel was not as devastating a blow as returning from the world of math. Why was that? After much thought, he reached a conclusion. No matter how clear things might become in the forest of story, there was never a clear-cut solution, as there was in math. The role of a story was, in the broadest terms, to transpose a problem into another form. Depending on the nature and the direction of the problem, a solution might be suggested in the narrative. Tengo would return to the real world with that suggestion in hand. It was like a piece of paper bearing the indecipherable text of a magic spell. It served no immediate practical purpose, but it contained a possibility.

The one possible solution that Tengo was able to decipher from his readings was this one: My real father must be somewhere else. Like an unfortunate child in a Dickens novel, Tengo had perhaps been led by strange circumstances to be raised by this impostor. Such a possibility was both a nightmare and a great hope. After reading “Oliver Twist,” Tengo plowed through every Dickens volume in the library. As he travelled through Dickens’s stories, he steeped himself in reimagined versions of his own life. These fantasies grew ever longer and more complex. They followed a single pattern, but with infinite variations. In all of them, Tengo would tell himself that his father’s home was not where he belonged. He had been mistakenly locked in this cage, and someday his real parents would find him and rescue him. Then he would have the most beautiful, peaceful, and free Sundays imaginable.

Tengo’s father prided himself on his son’s excellent grades, and boasted of them to people in the neighborhood. At the same time, however, he showed a certain displeasure with Tengo’s brightness and talent. Often when Tengo was at his desk, studying, his father would interrupt him, ordering the boy to do chores or nagging him about his supposedly offensive behavior. The content of his father’s nagging was always the same: here he was, running himself ragged every day, covering huge distances and enduring people’s curses, while Tengo did nothing but take it easy all the time, living in comfort. “They had me working my tail off when I was your age, and my father and older brothers would beat me black and blue for anything at all. They never gave me enough food. They treated me like an animal. I don’t want you thinking you’re so special just because you got a few good grades.”

This man is envious of me, Tengo began to think at a certain point. He’s jealous, either of me as a person or of the life I’m leading. But would a father really feel jealousy toward his son? Tengo did not judge his father, but he could not help sensing a pathetic kind of meanness emanating from his words and deeds. It was not that Tengo’s father hated him as a person but, rather, that he hated something inside Tengo, something that he could not forgive.

When the train left Tokyo Station, Tengo took out the paperback that he had brought along. It was an anthology of short stories on the theme of travel and it included a tale called “Town of Cats,” a fantastical piece by a German writer with whom Tengo was not familiar. According to the book’s foreword, the story had been written in the period between the two World Wars.

In the story, a young man is travelling alone with no particular destination in mind. He rides the train and gets off at any stop that arouses his interest. He takes a room, sees the sights, and stays for as long as he likes. When he has had enough, he boards another train. He spends every vacation this way.

One day, he sees a lovely river from the train window. Gentle green hills line the meandering stream, and below them lies a pretty little town with an old stone bridge. The train stops at the town’s station, and the young man steps down with his bag. No one else gets off, and, as soon as he alights, the train departs.

No workers man the station, which must see very little activity. The young man crosses the bridge and walks into the town. All the shops are shuttered, the town hall deserted. No one occupies the desk at the town’s only hotel. The place seems totally uninhabited. Perhaps all the people are off napping somewhere. But it is only ten-thirty in the morning, far too early for that. Perhaps something has caused all the people to abandon the town. In any case, the next train will not come until the following morning, so he has no choice but to spend the night here. He wanders around the town to kill time.

In fact, this is a town of cats. When the sun starts to go down, many cats come trooping across the bridge—cats of all different kinds and colors. They are much larger than ordinary cats, but they are still cats. The young man is shocked by this sight. He rushes into the bell tower in the center of town and climbs to the top to hide. The cats go about their business, raising the shop shutters or seating themselves at their desks to start their day’s work. Soon, more cats come, crossing the bridge into town like the others. They enter the shops to buy things or go to the town hall to handle administrative matters or eat a meal at the hotel restaurant or drink beer at the tavern and sing lively cat songs. Because cats can see in the dark, they need almost no lights, but that particular night the glow of the full moon floods the town, enabling the young man to see every detail from his perch in the bell tower. When dawn approaches, the cats finish their work, close up the shops, and swarm back across the bridge.

By the time the sun comes up, the cats are gone, and the town is deserted again. The young man climbs down, picks one of the hotel beds for himself, and goes to sleep. When he gets hungry, he eats some bread and fish that have been left in the hotel kitchen. When darkness approaches, he hides in the bell tower again and observes the cats’ activities until dawn. Trains stop at the station before noon and in the late afternoon. No passengers alight, and no one boards, either. Still, the trains stop at the station for exactly one minute, then pull out again. He could take one of these trains and leave the creepy cat town behind. But he doesn’t. Being young, he has a lively curiosity and is ready for adventure. He wants to see more of this strange spectacle. If possible, he wants to find out when and how this place became a town of cats.

On his third night, a hubbub breaks out in the square below the bell tower. “Hey, do you smell something human?” one of the cats says. “Now that you mention it, I thought there was a funny smell the past few days,” another chimes in, twitching his nose. “Me, too,” yet another cat says. “That’s weird. There shouldn’t be any humans here,” someone adds. “No, of course not. There’s no way a human could get into this town of cats.” “But that smell is definitely here.”

The cats form groups and begin to search the town like bands of vigilantes. It takes them very little time to discover that the bell tower is the source of the smell. The young man hears their soft paws padding up the stairs. That’s it, they’ve got me! he thinks. His smell seems to have roused the cats to anger. Humans are not supposed to set foot in this town. The cats have big, sharp claws and white fangs. He has no idea what terrible fate awaits him if he is discovered, but he is sure that they will not let him leave the town alive.

Three cats climb to the top of the bell tower and sniff the air. “Strange,” one cat says, twitching his whiskers, “I smell a human, but there’s no one here.”

“It is strange,” a second cat says. “But there really isn’t anyone here. Let’s go and look somewhere else.”

The cats cock their heads, puzzled, then retreat down the stairs. The young man hears their footsteps fading into the dark of night. He breathes a sigh of relief, but he doesn’t understand what just happened. There was no way they could have missed him. But for some reason they didn’t see him. In any case, he decides that when morning comes he will go to the station and take the train out of this town. His luck can’t last forever.

The next morning, however, the train does not stop at the station. He watches it pass by without slowing down. The afternoon train does the same. He can see the engineer seated at the controls. But the train shows no sign of stopping. It is as though no one can see the young man waiting for a train—or even see the station itself. Once the afternoon train disappears down the track, the place grows quieter than ever. The sun begins to sink. It is time for the cats to come. The young man knows that he is irretrievably lost. This is no town of cats, he finally realizes. It is the place where he is meant to be lost. It is another world, which has been prepared especially for him. And never again, for all eternity, will the train stop at this station to take him back to the world he came from.

Tengo read the story twice. The phrase “the place where he is meant to be lost” attracted his attention. He closed the book and let his eyes wander across the drab industrial scene passing by the train window. Soon afterward, he drifted off to sleep—not a long nap but a deep one. He woke covered in sweat. The train was moving along the southern coastline of the Boso Peninsula in midsummer.

One morning when he was in fifth grade, after much careful thinking, Tengo declared that he was going to stop making the rounds with his father on Sundays. He told his father that he wanted to use the time for studying and reading books and playing with other kids. He wanted to live a normal life like everybody else.

Tengo said what he needed to say, concisely and coherently.

His father, of course, blew up. He didn’t give a damn what other families did, he said. “We have our own way of doing things. And don’t you dare talk to me about a ‘normal life,’ Mr. Know-It-All. What do you know about a ‘normal life’?” Tengo did not try to argue with him. He merely stared back in silence, knowing that nothing he said would get through to his father. Finally, his father told him that if he wouldn’t listen then he couldn’t go on feeding him. Tengo should get the hell out.

Tengo did as he was told. He had made up his mind. He was not going to be afraid. Now that he had been given permission to leave his cage, he was more relieved than anything else. But there was no way that a ten-year-old boy could live on his own. When his class was dismissed at the end of the day, he confessed his predicament to his teacher. The teacher was a single woman in her mid-thirties, a fair-minded, warmhearted person. She heard Tengo out with sympathy, and that evening she took him back to his father’s place for a long talk.

Tengo was told to leave the room, so he was not sure what they said to each other, but finally his father had to sheathe his sword. However extreme his anger might be, he could not leave a ten-year-old boy to wander the streets alone. The duty of a parent to support his child was a matter of law.

As a result of the teacher’s talk with his father, Tengo was free to spend Sundays as he pleased. This was the first tangible right that he had ever won from his father. He had taken his first step toward freedom and independence.

At the reception desk of the sanatorium, Tengo gave his name and his father’s name.

The nurse asked, “Have you by any chance notified us of your intention to visit today?” There was a hard edge to her voice. A small woman, she wore metal-framed glasses, and her short hair had a touch of gray.

“No, it just occurred to me to come this morning and I hopped on a train,” Tengo answered honestly.

The nurse gave him a look of mild disgust. Then she said, “Visitors are supposed to notify us before they arrive to see a patient. We have our schedules to meet, and the wishes of the patient must also be taken into account.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know.”

“When was your last visit?”

“Two years ago.”

“Two years ago,” she said as she checked the list of visitors with a ballpoint pen in hand. “You mean to say that you have not made a single visit in two years?”

“That’s right,” Tengo said.

“According to our records, you are Mr. Kawana’s only relative.”

“That is correct.”

She glanced at Tengo, but she said nothing. Her eyes were not blaming him, just checking the facts. Apparently, Tengo’s case was not exceptional.

“At the moment, your father is in group rehabilitation. That will end in half an hour. You can see him then.”

“How is he doing?”

“Physically, he’s healthy. It’s in the other area that he has his ups and downs,” she said, tapping her temple with an index finger.

Tengo thanked her and went to wait in the lounge by the entrance, reading more of his book. A breeze passed through now and then, carrying the scent of the sea and the cooling sound of the pine windbreak outside. Cicadas clung to the branches of the trees, screeching their hearts out. Summer was at its height, but the cicadas seemed to know that it would not last long.

Eventually, the bespectacled nurse came to tell Tengo that he could see his father now. “I’ll show you to his room,” she said. Tengo got up from the sofa and, passing by a large mirror on the wall, realized for the first time what a sloppy outfit he was wearing: a Jeff Beck Japan Tour T-shirt under a faded dungaree shirt with mismatched buttons, chinos with specks of pizza sauce near one knee, a baseball cap—no way for a thirty-year-old son to dress on his first hospital visit to his father in two years. Nor did he have anything with him that might serve as a gift on such an occasion. No wonder the nurse had given him that look of disgust.

Tengo’s father was in his room, sitting in a chair by the open window, his hands on his knees. A nearby table held a potted plant with several delicate yellow flowers. The floor was made of some soft material to prevent injury in case of a fall. Tengo did not realize at first that the old man seated by the window was his father. He had shrunk—“shrivelled up” might be more accurate. His hair was shorter and as white as a frost-covered lawn. His cheeks were sunken, which may have been why the hollows of his eyes looked much bigger than they had before. Three deep creases marked his forehead. His eyebrows were extremely long and thick, and his pointed ears were larger than ever; they looked like bat wings. From a distance, he seemed less like a human being than like some kind of creature, a rat or a squirrel—a creature with some cunning. He was, however, Tengo’s father—or, rather, the wreckage of Tengo’s father. The father that Tengo remembered was a tough, hardworking man. Introspection and imagination might have been foreign to him, but he had his own moral code and a strong sense of purpose. The man Tengo saw before him was nothing but an empty shell.

“Mr. Kawana!” the nurse said to Tengo’s father in the crisp, clear tone she must have been trained to use when addressing patients. “Mr. Kawana! Look who’s here! It’s your son, here from Tokyo!”

Tengo’s father turned in his direction. His expressionless eyes made Tengo think of two empty swallow’s nests hanging from the eaves.

“Hello,” Tengo said.

His father said nothing. Instead, he looked straight at Tengo as if he were reading a bulletin written in a foreign language.

“Dinner starts at six-thirty,” the nurse said to Tengo. “Please feel free to stay until then.”

Tengo hesitated for a moment after the nurse left, and then approached his father, sitting down in the chair opposite his—a faded, cloth-covered chair, its wooden parts scarred from long use. His father’s eyes followed his movements.

“How are you?” Tengo asked.

“Fine, thank you,” his father said formally.

Tengo did not know what to say after that. Toying with the third button of his dungaree shirt, he turned his gaze toward the pine trees outside and then back again to his father.

“You have come from Tokyo, is it?” his father asked.

“Yes, from Tokyo.”

“You must have come by express train.”

“That’s right,” Tengo said. “As far as Tateyama. Then I transferred to a local for the trip here to Chikura.”

“You’ve come to swim?” his father asked.

“I’m Tengo. Tengo Kawana. Your son.”

The wrinkles in his father’s forehead deepened. “A lot of people tell lies because they don’t want to pay their NHK subscription fee.”

“Father!” Tengo called out to him. He had not spoken the word in a very long time. “I’m Tengo. Your son.”

“I don’t have a son,” his father declared.

“You don’t have a son,” Tengo repeated mechanically.

His father nodded.

“So what am I?” Tengo asked.

“You’re nothing,” his father said with two short shakes of the head.

Tengo caught his breath. He could find no words. Nor did his father have any more to say. Each sat in silence, searching through his own tangled thoughts. Only the cicadas sang without confusion, at top volume.

He may be speaking the truth, Tengo thought. His memory may have been destroyed, but his words are probably true.

“What do you mean?” Tengo asked.

“You are nothing,” his father repeated, his voice devoid of emotion. “You were nothing, you are nothing, and you will be nothing.”

Tengo wanted to get up from his chair, walk to the station, and go back to Tokyo then and there. But he could not stand up. He was like the young man who travelled to the town of cats. He had curiosity. He wanted a clearer answer. There was danger lurking, of course. But if he let this opportunity escape he would have no chance to learn the secret about himself. Tengo arranged and rearranged words in his head until at last he was ready to speak them. This was the question he had wanted to ask since childhood but could never quite manage to get out: “What you’re saying, then, is that you are not my biological father, correct? You are telling me that there is no blood connection between us, is that it?”

“Stealing radio waves is an unlawful act,” his father said, looking into Tengo’s eyes. “It is no different from stealing money or valuables, don’t you think?”

“You’re probably right.” Tengo decided to agree for now.

“Radio waves don’t come falling out of the sky for free like rain or snow,” his father said.

Tengo stared at his father’s hands. They were lined up neatly on his knees. Small, dark hands, they looked tanned to the bone by long years of outdoor work.

“My mother didn’t really die of an illness when I was little, did she?” Tengo asked slowly.

His father did not answer. His expression did not change, and his hands did not move. His eyes focussed on Tengo as if they were observing something unfamiliar.

“My mother left you. She left you and me behind. She went off with another man. Am I wrong?”

His father nodded. “It is not good to steal radio waves. You can’t get away with it, just doing whatever you want.”

This man understands my questions perfectly well. He just doesn’t want to answer them directly, Tengo thought.

“Father,” Tengo addressed him. “You may not actually be my father, but I’ll call you that for now because I don’t know what else to call you. To tell you the truth, I’ve never liked you. Maybe I’ve even hated you most of the time. You know that, don’t you? But, even supposing that there is no blood connection between us, I no longer have any reason to hate you. I don’t know if I can go so far as to be fond of you, but I think that at least I should be able to understand you better than I do now. I have always wanted to know the truth about who I am and where I came from. That’s all. If you will tell me the truth here and now, I won’t hate you anymore. In fact, I would welcome the opportunity not to have to hate you any longer.”

Tengo’s father went on staring at him with expressionless eyes, but Tengo felt that he might be seeing the tiniest gleam of light somewhere deep within those empty swallow’s nests.

“I am nothing,” Tengo said. “You are right. I’m like someone who’s been thrown into the ocean at night, floating all alone. I reach out, but no one is there. I have no connection to anything. The closest thing I have to a family is you, but you hold on to the secret. Meanwhile, your memory deteriorates day by day. Along with your memory, the truth about me is being lost. Without the aid of truth, I am nothing, and I can never be anything. You are right about that, too.”

“Knowledge is a precious social asset,” his father said in a monotone, though his voice was somewhat quieter than before, as if someone had reached over and turned down the volume. “It is an asset that must be amassed in abundant stockpiles and utilized with the utmost care. It must be handed down to the next generation in fruitful forms. For that reason, too, NHK needs to have all your subscription fees and—”

He cut his father short. “What kind of person was my mother? Where did she go? What happened to her?”

His father brought his incantation to a halt, his lips shut tight.

His voice softer now, Tengo went on, “A vision often comes to me—the same one, over and over. I suspect it’s not so much a vision as a memory of something that actually happened. I’m one and a half years old, and my mother is next to me. She and a young man are holding each other. The man is not you. Who he is I have no idea, but he is definitely not you.”

His father said nothing, but his eyes were clearly seeing something else—something not there.

“I wonder if I might ask you to read me something,” Tengo’s father said in formal tones after a long pause. “My eyesight has deteriorated to the point where I can’t read books anymore. That bookcase has some books. Choose any one you like.”

Tengo got up to scan the spines of the volumes in the bookcase. Most of them were historical novels set in ancient times when samurai roamed the land. Tengo couldn’t bring himself to read his father some musty old book full of archaic language.

“If you don’t mind, I’d rather read a story about a town of cats,” Tengo said. “It’s in a book that I brought to read myself.”

“A story about a town of cats,” his father said, savoring the words. “Please read that to me, if it is not too much trouble.”

Tengo looked at his watch. “It’s no trouble at all. I have plenty of time before my train leaves. It’s an odd story. I don’t know if you’ll like it.”

Tengo pulled out his paperback and started reading slowly, in a clear, audible voice, taking two or three breaks along the way to catch his breath. He glanced at his father whenever he stopped reading but saw no discernible reaction on his face. Was he enjoying the story? He could not tell.

“Does that town of cats have television?” his father asked when Tengo had finished.

“The story was written in Germany in the nineteen-thirties. They didn’t have television yet back then. They did have radio, though.”

“Did the cats build the town? Or did people build it before the cats came to live there?” his father asked, speaking as if to himself.

“I don’t know,” Tengo said. “But it does seem to have been built by human beings. Maybe the people left for some reason—say, they all died in an epidemic of some sort—and the cats came to live there.”

His father nodded. “When a vacuum forms, something has to come along to fill it. That’s what everybody does.”

“That’s what everybody does?”

“Exactly.”

“What kind of vacuum are you filling?”

His father scowled. Then he said with a touch of sarcasm in his voice, “Don’t you know?”

“I don’t know,” Tengo said.

His father’s nostrils flared. One eyebrow rose slightly. “If you can’t understand it without an explanation, you can’t understand it with an explanation.”

Tengo narrowed his eyes, trying to read the man’s expression. Never once had his father employed such odd, suggestive language. He always spoke in concrete, practical terms.

“I see. So you are filling some kind of vacuum,” Tengo said. “All right, then, who is going to fill the vacuum that you have left behind?”

“You,” his father declared, raising an index finger and thrusting it straight at Tengo. “Isn’t it obvious? I have been filling the vacuum that somebody else made, so you will fill the vacuum that I have made.”

“The way the cats filled the town after the people were gone.”

“Right,” his father said. Then he stared vacantly at his own outstretched index finger as if at some mysterious, misplaced object.

Tengo sighed. “So, then, who is my father?”

“Just a vacuum. Your mother joined her body with a vacuum and gave birth to you. I filled that vacuum.”

Having said that much, his father closed his eyes and closed his mouth.

“And you raised me after she left. Is that what you’re saying?”

After a ceremonious clearing of his throat, his father said, as if trying to explain a simple truth to a slow-witted child, “That is why I said, ‘If you can’t understand it without an explanation, you can’t understand it with an explanation.’ ”

Tengo folded his hands in his lap and looked straight into his father’s face. This man is no empty shell, he thought. He is a flesh-and-blood human being with a narrow, stubborn soul, surviving in fits and starts on this patch of land by the sea. He has no choice but to coexist with the vacuum that is slowly spreading inside him. Eventually, that vacuum will swallow up whatever memories are left. It is only a matter of time.

Tengo said goodbye to his father just before 6 P.M. While he waited for the taxi to come, they sat across from each other by the window, saying nothing. Tengo had many more questions he wanted to ask, but he knew that he would get no answers. The sight of his father’s tightly clenched lips told him that. If you couldn’t understand something without an explanation, you couldn’t understand it with an explanation. As his father had said.

When the time for him to leave drew near, Tengo said, “You told me a lot today. It was indirect and often hard to grasp, but it was probably as honest and open as you could make it. I should be grateful for that.”

Still his father said nothing, his eyes fixed on the view like a soldier on guard duty, determined not to miss the signal flare sent up by a savage tribe on a distant hill. Tengo tried looking out along his father’s line of vision, but all that was out there was the pine grove, tinted by the coming sunset.

“I’m sorry to say it, but there is virtually nothing I can do for you—other than to hope that the process forming a vacuum inside you is a painless one. I’m sure you have suffered a lot. You loved my mother as deeply as you knew how. I do get that sense. But she left, and that must have been hard on you—like living in an empty town. Still, you raised me in that empty town.”

A pack of crows cut across the sky, cawing. Tengo stood up, went over to his father, and put his hand on his shoulder. “Goodbye, Father. I’ll come again soon.”

With his hand on the doorknob, Tengo turned around one last time and was shocked to see a single tear escaping his father’s eye. It shone a dull silver color under the ceiling’s fluorescent light. The tear crept slowly down his cheek and fell onto his lap. Tengo opened the door and left the room. He took a cab to the station and reboarded the train that had brought him here.

(Translated, from the Japanese, by Jay Rubin.)

Quest’ultimo punto è ampiamente trattato in Mangascienza. Messaggi filosofici ed ecologici nell’animazione fantascientifica giapponese per ragazzi (Tunué, pp. 259, € 16,50; ora in offerta su Amazon.it cliccando qui a € 14,03), in cui Fabio Bartoli presenta lo sviluppo degli anime collegandolo ai paralleli cambiamenti che hanno mutato (e a volte sconvolto) il volto del Sol Levante. La storia di questo paese, soprattutto a partire dal 1868 – anno inaugurale dell’epoca Meiji e della modernizzazione – è stata caratterizzata da un rapporto ambiguo con la tecnologia: dapprima appresa in modo spasmodico guardando ai modelli europei e americani, poi subìta (soprattutto nel corso della seconda guerra mondiale; si veda la tragica esperienza delle bombe atomiche), infine integrata nel quotidiano.

Quest’ultimo punto è ampiamente trattato in Mangascienza. Messaggi filosofici ed ecologici nell’animazione fantascientifica giapponese per ragazzi (Tunué, pp. 259, € 16,50; ora in offerta su Amazon.it cliccando qui a € 14,03), in cui Fabio Bartoli presenta lo sviluppo degli anime collegandolo ai paralleli cambiamenti che hanno mutato (e a volte sconvolto) il volto del Sol Levante. La storia di questo paese, soprattutto a partire dal 1868 – anno inaugurale dell’epoca Meiji e della modernizzazione – è stata caratterizzata da un rapporto ambiguo con la tecnologia: dapprima appresa in modo spasmodico guardando ai modelli europei e americani, poi subìta (soprattutto nel corso della seconda guerra mondiale; si veda la tragica esperienza delle bombe atomiche), infine integrata nel quotidiano. *Regolamento del gruppo di lettura*

*Regolamento del gruppo di lettura* Se per molti questo sarà un weekend di riposo o di scampagnate (tempo permettendo), per altri passerà all’insegna di Halloween e dei brividi. Oggi vi propongo dunque un thriller, ambientato tra Europa e Giappone in una delle epoche più buie della storia umana, ossia durante il nazismo. Il libro in questione è Il Signore delle cento ossa della scrittrice Ben Pastor (Sellerio, pp. 416, € 14; ora in offerta su Amazon.it

Se per molti questo sarà un weekend di riposo o di scampagnate (tempo permettendo), per altri passerà all’insegna di Halloween e dei brividi. Oggi vi propongo dunque un thriller, ambientato tra Europa e Giappone in una delle epoche più buie della storia umana, ossia durante il nazismo. Il libro in questione è Il Signore delle cento ossa della scrittrice Ben Pastor (Sellerio, pp. 416, € 14; ora in offerta su Amazon.it  Per definire il Novecento, Eric J. Hobsbawm ha parlato di “secolo breve”, caratterizzato da profonde trasformazioni politiche, economiche e sociali. Molte delle sue contraddizioni e, soprattutto, dei suoi nodi irrisolti sorsero però già nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento: mentre lo “spettro del comunismo” – riprendendo le parole di Marx – s’aggirava per l’Europa e i popoli (compreso quello italiano) combattevano per l’autodeterminazione, da qualche botteguccia del porto di Yokohama giunsero nel Vecchio continente migliaia e migliaia di insolite statuette, grandi poco meno d’un pugno. Erano di legno di bosso, argilla, ceramica, osso; potevano raffigurare un monaco mendicante, una tigre spaventosa e innumerevoli altri soggetti da legare alla cintola del kimono.

Per definire il Novecento, Eric J. Hobsbawm ha parlato di “secolo breve”, caratterizzato da profonde trasformazioni politiche, economiche e sociali. Molte delle sue contraddizioni e, soprattutto, dei suoi nodi irrisolti sorsero però già nella seconda metà dell’Ottocento: mentre lo “spettro del comunismo” – riprendendo le parole di Marx – s’aggirava per l’Europa e i popoli (compreso quello italiano) combattevano per l’autodeterminazione, da qualche botteguccia del porto di Yokohama giunsero nel Vecchio continente migliaia e migliaia di insolite statuette, grandi poco meno d’un pugno. Erano di legno di bosso, argilla, ceramica, osso; potevano raffigurare un monaco mendicante, una tigre spaventosa e innumerevoli altri soggetti da legare alla cintola del kimono. «Un libro fantastico. Con umorismo sardonico e stile hardboiled, Adelstein accompagna il lettore in un viaggio appassionante nel mondo del crimine giapponese, esaminando i rapporti spesso ambigui tra giornalisti, poliziotti e gangster». Così George Pelecanos, significativo scrittore noir statunitense, ha commentato Tokyo Vice di Jake Adelstein (Einaudi, pp. 466, € 19,50), volume da poco uscito in Italia e ispirato a una storia vera dalle tinte forte. Questa la presentazione dell’editore:

«Un libro fantastico. Con umorismo sardonico e stile hardboiled, Adelstein accompagna il lettore in un viaggio appassionante nel mondo del crimine giapponese, esaminando i rapporti spesso ambigui tra giornalisti, poliziotti e gangster». Così George Pelecanos, significativo scrittore noir statunitense, ha commentato Tokyo Vice di Jake Adelstein (Einaudi, pp. 466, € 19,50), volume da poco uscito in Italia e ispirato a una storia vera dalle tinte forte. Questa la presentazione dell’editore: At Koenji Station, Tengo boarded the Chuo Line inbound rapid-service train. The car was empty. He had nothing planned that day. Wherever he went and whatever he did (or didn’t do) was entirely up to him. It was ten o’clock on a windless summer morning, and the sun was beating down. The train passed Shinjuku, Yotsuya, Ochanomizu, and arrived at Tokyo Central Station, the end of the line. Everyone got off, and Tengo followed suit. Then he sat on a bench and gave some thought to where he should go. “I can go anywhere I decide to,” he told himself. “It looks as if it’s going to be a hot day. I could go to the seashore.” He raised his head and studied the platform guide.

At Koenji Station, Tengo boarded the Chuo Line inbound rapid-service train. The car was empty. He had nothing planned that day. Wherever he went and whatever he did (or didn’t do) was entirely up to him. It was ten o’clock on a windless summer morning, and the sun was beating down. The train passed Shinjuku, Yotsuya, Ochanomizu, and arrived at Tokyo Central Station, the end of the line. Everyone got off, and Tengo followed suit. Then he sat on a bench and gave some thought to where he should go. “I can go anywhere I decide to,” he told himself. “It looks as if it’s going to be a hot day. I could go to the seashore.” He raised his head and studied the platform guide. face of adversity. To someone who had barely eaten a filling meal since birth, collecting NHK fees was not excruciating work. The most hostile curses hurled at him were nothing. Moreover, he felt satisfaction at belonging to an important organization, even as one of its lowest-ranking members. His performance and attitude were so outstanding that, after a year as a commissioned collector, he was taken directly into the ranks of the full-fledged employees, an almost unheard-of achievement at NHK. Soon, he was able to move into a corporation-owned apartment and join the company’s health-care plan. It was the greatest stroke of good fortune he had ever had in his life.

face of adversity. To someone who had barely eaten a filling meal since birth, collecting NHK fees was not excruciating work. The most hostile curses hurled at him were nothing. Moreover, he felt satisfaction at belonging to an important organization, even as one of its lowest-ranking members. His performance and attitude were so outstanding that, after a year as a commissioned collector, he was taken directly into the ranks of the full-fledged employees, an almost unheard-of achievement at NHK. Soon, he was able to move into a corporation-owned apartment and join the company’s health-care plan. It was the greatest stroke of good fortune he had ever had in his life. Una bellissima notizia per tutti gli amanti della letteratura giapponese contemporanea: da una settimana è disponibile in libreria La vergine eterna (trad. di Gianluca Coci, Garzanti, pp. 252, € 18,50;

Una bellissima notizia per tutti gli amanti della letteratura giapponese contemporanea: da una settimana è disponibile in libreria La vergine eterna (trad. di Gianluca Coci, Garzanti, pp. 252, € 18,50;