Haruki Murakami is quite possibly the most successful and influential cult author in the world today. The 59-year-old sells millions of books in Japan. His fifth novel, Norwegian Wood, sold more than 3.5m copies in its first year and his work has been translated into 40 languages, in which he sells almost as well. Last year’s novella, After Dark, shifted more than 100,000 copies in English in its first three months. His books are like Japanese food — a mix of the delicate, the deliberately bland and the curiously exotic. Dreams, memory and reality swap places, all leavened with dry humour. His translator, Professor Jay Rubin, says reading Murakami changes your brain. His world-view has inspired Sofia Coppola, the author David Mitchell and American bands such as the Flaming Lips. He is a recipient of the Franz Kafka prize, has honorary degrees from Princeton and Liège, and is tipped for the Nobel prize for literature.

MURAKAMI DIVIDES PEOPLE

In June 2000, the panel members of German television’s literary review show Das Literarische Quartett disagreed so violently about his writing that one of them quit after 12 years on the programme. Opinion is equally divided in Japan. While younger readers adore him and even choose to study at his alma mater, Waseda University, in the hope of living in the dorm he describes in Norwegian Wood, he is viewed as pop, trashy and overly westernised by Japan’s literary establishment, who prefer the formal writing of Mishima, Tanizaki or Kawabata. Born in Kyoto in 1949, he studied theatre arts at Waseda — although the course didn’t interest him hugely and he spent much of his time reading film scripts in the library. He was hugely influenced by the student rebellions in 1968, which find their way into many of his novels. As a result, he’s a typical baby boomer — openly critical of Japan’s obsession with capitalism. He finds Japanese traditions boring. This doesn’t go down very well.

MURAKAMI IS HUGELY INFLUENTIAL

As well as countless Japanese novelists, the plot and style of Sofia Coppola’s Lost in Translation were partly inspired by Murakami’s novels. David Mitchell — twice nominated for the Booker prize — owes a huge debt to him after reading him while teaching in Japan. Indeed, the title of his second novel, Number 9 Dream, is a veiled tribute to Norwegian Wood — both were named after Beatles songs. Among others, the Complicite theatre company adapted The Elephant Vanishes in 2003; Robert Wyatt reads from Murakami’s books on Max Richter’s 2006 album Songs from Before; and the Grateful Dead-style jam band Sound Tribe Sector 9 soundtracked a 2007 film version of the story All God’s Children Can Dance.

HIS BOOKS WOULD NOT MAKE A HIGH-CONCEPT MOVIE PITCH

Imagine that JD Salinger and Gabriel Garcia Marquez had collaborated on a manga version of The Maltese Falcon. Norwegian Wood is the Japanese equivalent of The Catcher in the Rye — required reading for every troubled adolescent. Curiously, Murakami translated The Catcher in the Rye into Japanese and found it good but incomplete. “The story becomes darker and darker, and Holden Caulfield doesn’t find his way out of the dark world,” he argues. “I think Salinger himself didn’t find it either.” Murakami balances the mundane — intimate descriptions of preparing and eating simple meals feature regularly — with the fantastic. His protagonists are usually ordinary people trying to get by in life, until some type of ethereal male guide steers them into a new direction, sometimes quite literally. In All God’s Children Can Dance, Yoshiya, a young man working at a publishing company, wakes up with a crushing hangover and heads to his office hours later than usual. On the train coming home that night, he sees an older man who has the distinguishing features of his absent father. Yoshiya follows this man on the train, then through darkened, empty streets, to find himself in a deserted baseball diamond at night. The man vanishes, and Yoshiya stands on the pitcher’s mound in the cold wind and simply dances.

MURAKAMI IS CONFLICTED ABOUT HIS HOMELAND

Both his parents taught Japanese literature, but he preferred reading second-hand pulp-fiction novels picked up in the port city of Kobe. He is a devoted fan of western music and hates the formalism of Mishima. In 1987, the huge success of Norwegian Wood made him an overnight celebrity, which terrified and annoyed him. In December 1988, he left the country, becoming a writing fellow at Princeton. A Japanese weekly magazine reported his departure under the headline “Haruki Murakami has escaped from Japan”. Published in 1994, The Wind-up Bird Chronicle picked apart the cultural groupthink that led Japan into the second world war, a theme he revisited in his first nonfiction book, Underground (published in 1997), about the Tokyo subway attacks by the Aum Shinrikyo cult. He worries about Japan’s tendency to forget wartime atrocities. Even so, he says: “Before, I wanted to be an expatriate writer. But I am a Japanese writer. This is my soil and these are my roots. You cannot get away from your country.”

MURAKAMI USED TO RUN A JAZZ CLUB

He owned it from the end of his university years until 1981, when he was able to support himself with his writing. The experience may have contributed to the negative role of drinking in his books. He uses alcohol as a signifier of the petty, the negative and the evil. That is not to say he is teetotal. He loves beer, rewarding himself with a cold one for feats of writing or sporting endurance. Perhaps it was the crushed, social blend of booze and crowds that made Murakami uneasy. He once said: “When I had the club, I stood behind the bar, and it was my job to engage in conversation. I did that for seven years, but I’m not a talkative person. I swore to myself, once I’ve finished here, I will only ever talk to those people I really want to talk to.” As a result, he refuses to appear on radio or television.

MURAKAMI OWES EVERYTHING TO BASEBALL

On April 1, 1978, he was watching a baseball game at the Jingu Stadium, in Tokyo, on a warm, sunny day — the Yakult Swallows against the Hiroshima Carp. An American player for the Swallows, Dave Hilton, stepped up to bat and hit a home run. In that instant, Murakami knew he was going to write a novel. “It was a warm sensation. I can still feel it in my heart,” he told Der Spiegel earlier this year. He started work that night on his debut novel, Hear the Wind Sing. It has many Murakami themes: there are animals; the hero is a young man, rather isolated, laconic, operating on cruise control and jobless; his eventual girlfriend has a twin (Murakami likes doppelgängers); cooking, eating, drinking and listening to western music are described often and in detail; and the plot is both incredibly simple and bafflingly complex. Writing while running a jazz bar proved difficult, however, and it is a fragmented, jumpy read. The unpublished manuscript won first prize in a competition run by the influential Japanese literary magazine Gunzo, but Murakami himself doesn’t like it very much and didn’t want it translated into English.

MURAKAMI LIKES CATS

His jazz bar was called Peter Cat, and cats appear in many of his stories — usually indicating that something very strange is about to happen. It’s a missing cat that starts off the whole surreal chain of events in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle, while Kafka on the Shore features a confused and possibly brain-damaged pensioner called Nakata, who, after a mysterious incident involving a strange silver light at the end of the second world war, fell into a coma and woke to find that he had telepathic communication with cats. This, it turns out, is fortunate, as a conversation with an unusually bright member of the species, who is on the run from a strange cat-catcher called Johnnie Walker, ultimately leads to Nakata preventing the living embodiment of pure evil from destroying the planet. As I said, something very strange.

MURAKAMI REALLY LIKES MUSIC

Many of his book titles are musical references: Norwegian Wood after the Beatles song, South of the Border, West of the Sun after a Nat King Cole track and Dance, Dance, Dance after the Beach Boys tune. The three books in The Wind-up Bird Chronicle are named after a Rossini overture, a piano piece by Schumann and a character in Mozart’s Magic Flute respectively. In Kafka on the Shore, the hero’s contact with the spirit of a dead woman who has obsessed him throughout the novel finally comes about when he discovers a cache of vinyl records in a desolate library on the outskirts of a regional city and plays Beethoven’s Archduke Trio. In Pinball, 1973, revolutionary students occupying a university building find a classical-music library and spend every evening listening to records. One beautifully clear November afternoon, riot police force their way into the building while Vivaldi’s L’Estro armonico blares at full volume. One interviewer visited Murakami’s flat and found a room lined with more than 7,000 vinyl records.

MURAKAMI REALLY, REALLY LIKES RUNNING

His latest book, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, is the closest thing he’s written to an autobiography (although some fans suspect Norwegian Wood has more than a little of his own life at its core). In this extended monologue, Murakami reminisces about his life as seen through the prism of the sport.

He began running at the age of 33 to lose weight after giving up smoking. Within a year, he had run his first marathon. He’s also run the original marathon, between Marathon and Athens — albeit in reverse, because he didn’t want to arrive in Athens during the rush hour. His personal best time for a marathon is 3hr 27min, in New York in 1991. In 1995, he ran in a 100km ultramarathon. It took him more than 11 hours and he nearly collapsed halfway through. He describes his second wind as a religious experience, but decided that he wouldn’t run another one. He believes that “a fortunate author can write maybe 12 novels in his lifetime. I don’t know how many good books I still have in me. I hope there are another four or five. When I am running, I don’t feel that limit. I publish a thick novel every four years, but I run a 10km race, a half-marathon and a marathon every year”. He gets up at 4am, writes for four hours, then runs 10km. On his tombstone, he would like the phrase “at least he never walked”.

MURAKAMI IS A ROMANTIC

His protagonists are usually transformed by exquisitely tender physical unions with unusual, beautiful and often confused or mysterious women. He describes love with delicate wonder, and his hero is driven by passionate need once the woman of his life is revealed. “I have to talk to you,” Norwegian Wood’s Toru Watanabe tells the emotionally troubled Naoko. “I have a million things to talk to you about. All I want in this world is you. I want to see you and talk. I want the two of us to begin everything from the beginning.”

Yet it usually doesn’t work out. Murakami’s women are often spirits or extremely fragile. They write the hero long, rambling letters from afar and either attempt suicide or manage to kill themselves during the course of the novel. In one case, the love interest turns out to be the ghost of the hero’s mother, captured when she was a teenage girl. Murakami himself has been married since 1971 to Yoko, although he has speculated in interviews about whether this was the right thing to do. “Unlike my wife, I don’t like company. I have been married for 37 years and often it is a battle,” he told Der Spiegel. ”I am used to being alone. And I enjoy being alone.”

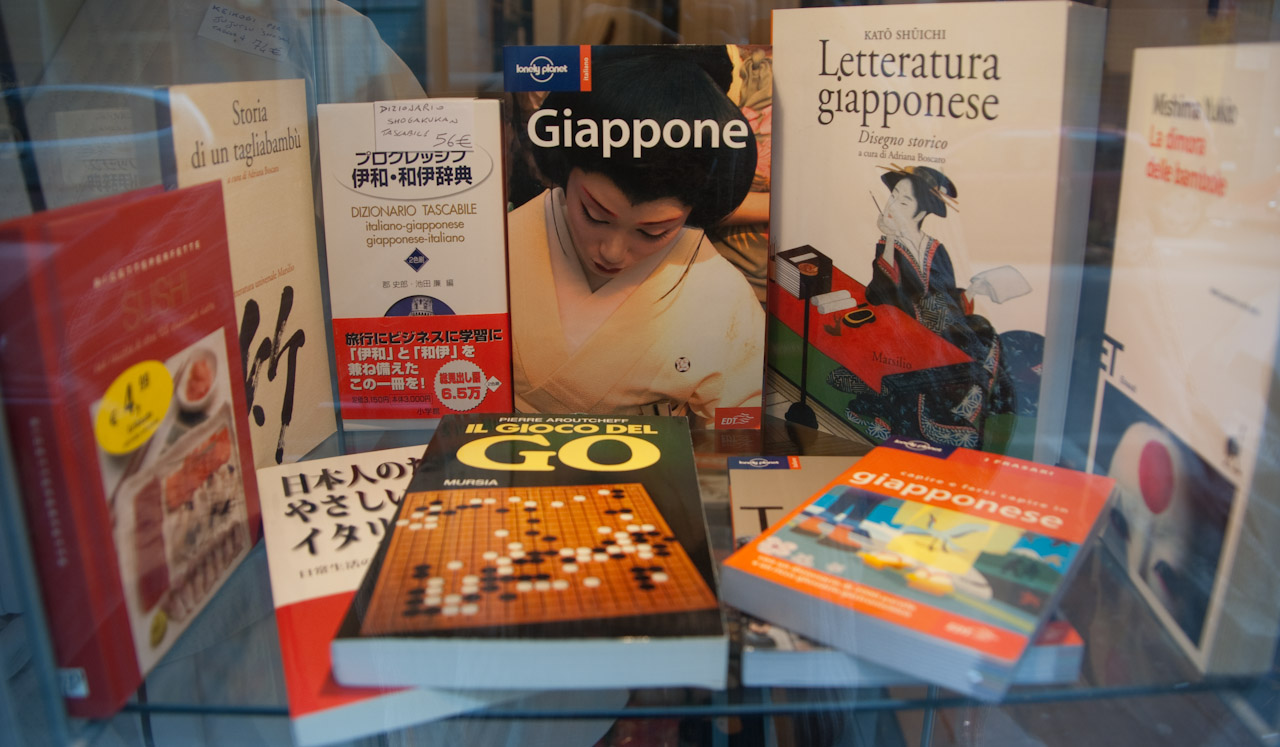

Il quartiere Shibuya è senz’altro uno dei più noti di Tokyo; è conosciuto per l’ampia area commerciale e la folla spesso appariscente, costituita in larga parte di giovani. Uno dei principali simboli della zona è sicuramente la celebre statua di Hachiko, il cane che aspettò tutte le sere per undici anni il suo padrone alla stazione della metro, inconsapevole della sua morte.

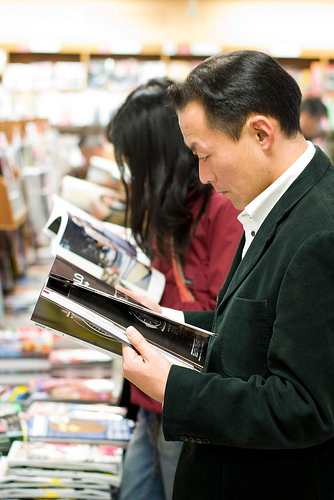

Il quartiere Shibuya è senz’altro uno dei più noti di Tokyo; è conosciuto per l’ampia area commerciale e la folla spesso appariscente, costituita in larga parte di giovani. Uno dei principali simboli della zona è sicuramente la celebre statua di Hachiko, il cane che aspettò tutte le sere per undici anni il suo padrone alla stazione della metro, inconsapevole della sua morte. Dopo anni di convinta e piuttosto spudorata lettura a scrocco in libreria, non può che farmi piacere scoprire il medesimo hobby in un’ampia porzione di giapponesi.

Dopo anni di convinta e piuttosto spudorata lettura a scrocco in libreria, non può che farmi piacere scoprire il medesimo hobby in un’ampia porzione di giapponesi.